Civic Revival:

Building on a tradition of enlightened localism

We make no claim at Civic Revival to be the first, or even a particularly significant, element in the tradition of individual and collective thinking about the best and most productive way for citizens to be involved in their communities, and in the choices to be made about how the places they inhabit evolve and develop better with their help, enthusiasm and combined energies.

But the fact that there is such a tradition is obvious and important to us.

Historically, the growth of structured human settlements – villages, towns and then cities – began the discussion about how they are shaped and their control and governance. Indeed, the very concept of civilisation.

Various epochs are well-known for their importance in the shaping of civic life, for example the Ancient Greek and Roman approaches to both the management and democratic processes for city habitation, and the similar early civilisations of the Middle East, Latin America and other parts of the world.

We still embrace some of those early concepts of civic responsibility, the rights and roles of citizens, and the idea of municipal endeavour, and collectively shared and curated resources. Philosophers and social reformers have a long tradition of espousing the concept of ‘civic virtue’-by which they mean the harvesting of habits important for the success of a community. Closely linked to the concept of citizenship, civic virtue is often conceived as the dedication of citizens to the common welfare of their community, even at the cost of their individual interests. The identification of the character traits that constitute civic virtue has been a major concern of political philosophy. Indeed, the term civility refers to behaviour between persons and groups that conforms to a social mode (that is, in accordance with the civil society), as itself being a foundation of society and law.

Creating good places to live

For quite a long time, the major demonstration of civic structure was in buildings and monumental architecture – not in the mundane issue of the housing of ordinary people and provision of their community facilities and opportunity for expressive and creative activity. However, over time some imaginative and innovate architects and developers at least sought to create well-structured and laid out communities catering for both living accommodation and a shared public realm. For example, the work of James and Decimus Burton, father and son developers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of the new town of St Leonards on Sea next door to Civic Revival’s southern home at Hastings. This area includes areas designated as the housing for both the wealthy and their domestic servants, including mercatoria (the trading and merchant area) and lavatoria (the washing and maintenance quarter).

A less laudable trend was the establishment of poor quality, quickly built and unattractively laid out cramped housing areas in the new industrial mill towns in the north of England, a feature of areas around our northern home Bolton, during the nineteenth-century industrial revolution.

Better examples of more generously created communities for the expanded working populations linked to Victorian industrial enterprise are Bourneville near Birmingham, the estate of chocolate magnate John Cadbury; Saltaire in West Yorkshire, around the textile mills of Titus Salt; and Port Sunlight near Liverpool, the creation of Lord Lever around his soap-making factories.

Establishing municipal governance

Alongside the development of urban settlements and the physical structure of ‘places’, a parallel key issue has been the matter of democracy and representation of the populace. Such governance is usually discussed in the context of ‘enfranchisement’ at national level, and the idea of citizens voting for their governments. Or perhaps better described initially as ‘some citizens’ being allowed to vote, with universal suffrage being only a quite recent development.

But it’s also worth noting that ‘local democracy’, as we understand it today, also has a relatively short history, with English municipal corporations only being established as bodies responsible to their citizens since the mid-19th century. And in particular the enactment of The Municipal Corporations Act in 1835 in the wake of The Great Reform Act of 1832, and subsequently The Local Government Act of 1888.

By 1888, it was clear that the piecemeal system that had developed over the previous century in response to a vastly increased need for local administration as industrialisation and urbanisation continued apace, could no longer cope. The sanitary districts and parish councils had legal status, but were not part of the mechanism of government. They were run by volunteers; often there was no-one who could be held responsible for the failure to undertake the required duties, as in the reformed municipal boroughs. The Local Government Act was therefore the first systematic attempt to impose a standardised system of local government in England

The 1888 act established statutory county councils as well as newly defined areas for those councils. The new administrative counties were based on England’s historic counties, which had been used in the local government structure until then. These statutory administrative counties were also to be used for non-administrative functions: "sheriff, lieutenant, custos rotulorum, justices, militia, coroner, or other". With the advent of elected councils, the offices of lord lieutenant and sheriff became largely ceremonial.

However, it was felt that large cities and primarily rural areas in the same county could not be well administered by the same body. Thus 59 “counties in themselves”, or “county boroughs”, were created to administer the urban centres of England. These were part of the statutory counties, but not part of the administrative counties. The qualifying limit for county borough status was a population of 50,000, although some historic county towns were given county borough status such as Canterbury and Oxford. Each county borough and administrative county was to be governed by an elected county or borough council, providing services specifically for those areas. The act also created a (metropolitan) County of London from the rapidly growing urbanised area of London, which was a full statutory county by itself. This county absorbed the Metropolitan Board of Works, which had been established in 1855 to maintain the infrastructure of London.

Many towns had historically possessed liberties and franchises from royal charters and grants which were mostly anomalous, obsolete or otherwise irrelevant under the new structure, though (for instance to hold markets) nevertheless often cherished by the townspeople. Some of these towns were municipal boroughs, in which case the powers remained with the municipal corporation. However, there were others (such as the towns of the Cinque Ports on the south coast)which were not boroughs. Rather than abolish these rights and powers, the act directed that the powers should be taken over by the new county council; and vested in the county (or county borough) council.

A second Act in 1894 (Local Government Act 1894) also created a second tier of local government. Henceforth, all administrative counties and county boroughs would be divided into either rural or urban districts, allowing more localised administration. The municipal boroughs reformed after 1835 were brought into this system as special cases of urban districts. The urban and rural districts were based upon, and incorporated, the sanitary districts which had been created in 1875.

The Act also provided for the establishment of civil parishes, separated from the ecclesiastical parishes, to carry on some of these responsibilities (others being transferred to the district/county councils). However, the civil parishes were not a complete third-tier of local government. Instead, they were 'community councils' for smaller, rural settlements, which did not have a local government district to themselves. The act automatically created them in all settlements with more than 300 residents in rural districts; whilst settlements with between 100-300 residents could apply to form a civil parish. Where urban parish councils had previously existed, they were absorbed into the new urban districts.

A final relevant piece of legislation, the London Government Act 1899, divided the new County of London into districts, known as Metropolitan Boroughs.

Expressing civic values

Alongside the evolving Local Government structures, the twin concepts of municipal enterprises and of town planning were also beginning to emerge – particularly with the rapid industrial, social and economic change that characterisedthe Victorian era and beginning of the 20th century.

Municipally-organised services included tramways, omnibuses, gas, water and electricity etc; plus often grand and distinctive town halls and other buildings like bathhouses and swimming pools – sometimes built by public subscription – allotments, parks and playing fields and so on.

As far as town planning is concerned. early candidates for civic heroes in this regard must include Sir Patrick Geddes (1854 – 1932), who was a British biologist, sociologist, geographer, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He is particularly known for his innovative thinking in the fields of urban planning and sociology. He introduced the concept of "region" to architecture and planning, and coined the term "conurbation". Later, he elaborated "neotechnics" as the way of remaking a world beyond over-commercialisation and money dominance.

While he thought of himself primarily as a sociologist, it was his commitment to close social observation and ability to turn this into practical solutions for city design and improvement that earned him a revered place amongst the founding fathers of the British town planning and civic improvement movements. He was a major influence on the American urban theorist Lewis Mumford.

Geddes adopted Herbert Spencer's theory that the concept of biological evolution could be applied to explain the evolution of society too, and drew on Frederic Le Play's analysis of the key units of society as constituting "Lieu, Travail, Famille" ("Place, Work, Family"), though he changed the last from "family" to "folk". In this theory, the family is viewed as the central "biological unit of human society" from which all else develops. According to Geddes, it is from "stable, healthy homes", providing the necessary conditions for mental and moral development, that come beautiful and healthy children who are able "to fully participate in life".

Geddes drew on Le Play's circular theory of geographical locations presenting environmental limitations and opportunities that in turn determine the nature of work. His central argument was that physical geography, market economics and anthropology were related, yielding a “single chord of social life [of] all three combined”. Thus the interdisciplinary subject of sociology was developed into the science of “man’s interaction with a natural environment: the basic technique was the regional survey, and the improvement of town planning the chief practical application of sociology".

Geddes' writing demonstrates the influence of these ideas on his theories of the city. He saw the city as a series of common interlocking patterns, "an inseparably interwoven structure", akin to a flower. These ideas can also be traced back to Geddes' abiding interest in Eastern philosophy which he believed more readily conceived of "life as a whole": "as a result, civic beauty in India has existed at all levels, from humble homes and simple shrines to palaces magnificent and temples sublime," he wrote. He criticised the tendency of modern scientific thinking to specialisation. In his "Report to the H.H. the Maharaja of Kapurthala" in 1917 he wrote:

"Each of the various specialists remains too closely concentrated upon his single specialism, too little awake to those of the others. Each sees clearly and seizes firmly upon one petal of the six-lobed flower of life and tears it apart from the whole."

Against a backdrop of extraordinary development of new technologies, industrialisation and urbanism, Geddes witnessed the substantial social consequences of crime, illness and poverty that developed. From Geddes' perspective, the purpose of his theory and understanding of relationships among the units of society early was to find an equilibrium among people and the environment to improve such conditions – a fine example of early ‘civic thinking’.

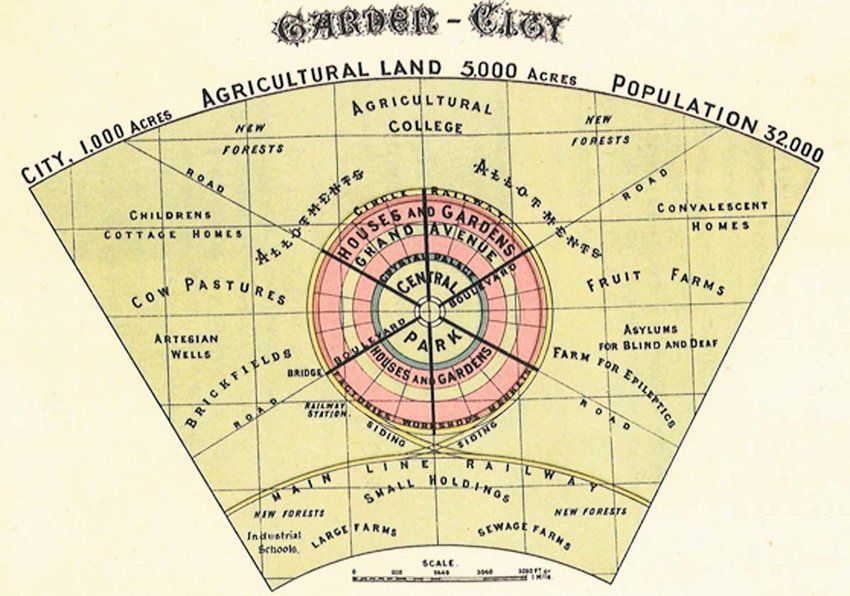

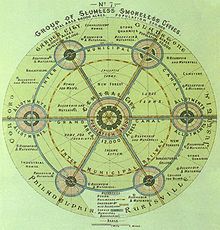

Another widely acknowledged local civic hero is Sir Ebenezer Howard (1850 – 1928), an English urban planner and founder of the garden city movement, known for his publication To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), the description of a utopian city in which people live harmoniously together with nature.

In 1899 Howard founded the Garden Cities Association, known now as the Town and Country Planning Association. His 1902 book Garden Cities of Tomorrow proposed that society be reorganised with networks of garden cities that would break the stronghold of capitalism and lead to cooperative socialism. It proposed the creation of new suburban towns of limited size, planned in advance, and surrounded by a permanent belt of agricultural land.

By his association with Henry Harvey Vivian, and the co-partnership housing movement, his ideas attracted enough attention and funding to give birth to Letchworth Garden City, the first suburban garden city 37 miles north of London on which work began in 1903. In 1901, under the guidance of Vivian, a new co-partnership housing development venture had been started in the London Borough of Ealing that was to become the Brentham Garden Suburb, now a conservation area. A second garden city, Welwyn Garden City, was started after World War I in the 1920’s.

The creation of Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City were influential for the development of other "New Towns" after World War II. This concept produced more than 30 communities conceived and designed from scratch, the first being Stevenage, Hertfordshire in the 1950’s, and the last (and largest) being Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire in the 1970’s. Howard's ideas also influenced other planners such as Frederick Law Olmsted II and Clarence Perry. Developments in other countries included Forest Hills in New York, Radburn in New Jersey, and others in the USA. Walt Disney even used elements of Howard's concepts in his original design for his EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) attraction in Florida.

In 1913 Howard founded the 'Garden Cities and Town Planning Association' – presently the International Federation for Housing and Planning. Its goal was to promote the concept of planned housing and to improve the general standard of the profession by the international exchange of knowledge and experience.

Howard read widely, including Edward Bellamy's 1888 utopian novel, Looking Backward, and Henry George's economic treatise, Progress and Poverty, and thought much about social issues. He disliked the way modern cities were being developed and thought people should live in places that combined the best aspects of both cities and the countryside, and aimed to reduce the alienation of humans and society from nature. He wanted Garden Cities to avoid the downsides of industrial cities of the time such as urban squalor, poverty, overcrowding, low wages, dirty streets with no drainage, poorly ventilated houses, dust and toxic substances, infectious disease and lack of fresh air and interaction with nature. He illustrated the idea with his famous Three Magnets diagram (pictured), which addressed the question 'Where will the people go?', the choices being 'Town', 'Country' or 'Town-Country'.

His ideal towns would be largely independent, managed by the citizens who had an economic interest in them, and financed by ground rents on the Georgist model. The land on which they were to be built was to be owned by a group of trustees and leased to the citizens.

While many believe the diagrams and designs in Howard's Garden Cities of Tomorrow to be a physical plan for the perfect garden city, Howard wanted these to be merely suggestive as each city should be planned to be organised to suit the needs of the people and their particular environment.

Asserting people power

Another significant thread in the journey towards the concept of local community empowerment and engagement was the emergence of Civic Societies.

The aforementioned Patrick Geddes, in fact, became a ‘guide and advisor’ to the first generation of individuals to establish town planning as a professional activity in Britain (named in legislation for the first time in 1909), and led discussion on the layout of cities, their architectural distinctiveness and their planning for continued growth.

This increasing interest in planning and the betterment of urban life provided focus and momentum for the civic movement. Indeed, in her history of the Civic Society Movement published in 2014 by Civic Voice, Lucy E Hewitt observes that early civic societies were often linked to the increasing profile and professionalisation of planning. The Liverpool City Guild, for example, was formed in 1910 as part of a number of initiatives in the city. Following a bequest made by industrialist, philanthropist and founder of Port Sunlight, William Hesketh Lever, the University of Liverpool established the first Department of Civic Design in 1909. The bequest also supported a research post, occupied by Patrick Abercrombie whose later career dominated planning in Britain during the second quarter of the twentieth century. The Liverpool City Guild was formed at this point by figures including Stanley Adshead (who held the first Chair of Civic Design at the University of Liverpool) and Abercrombie. Early reports of the Guild’s discussions and activities were also published in the Town Planning Review, demonstrating how closely connected with broader developments in planning early civic societies could be, notes Lucy Hewitt.

In some cases early professionals sought to extend the use of new planning methods through voluntary activity. For example, the London Society was founded in January 1912 in response to the new planning powers granted to local authorities under the 1909 Act and, particularly, to the reluctance of the London County Council to utilise them. Hewitt notes that crucially, while the 1909 Act enabled local authorities to prepare planning schemes within their administrative boundaries, no mechanism for organised planning across Britain’s conurbations existed, posing the potential for chaos resulting out of many discrete and uncoordinated attempts at development. The planners, architects and politicians involved in the London Society took part in discussions with various urban and rural district authorities in the Greater London region, and during the First World War went on to produce a plan showing the potential routes for arterial roads which could serve as a network for the whole of Greater London.

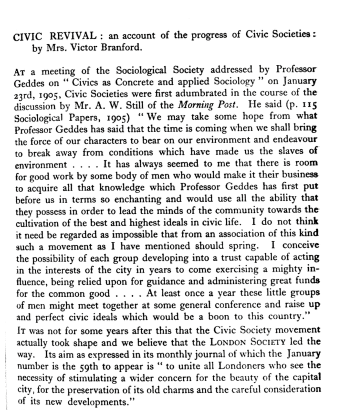

An interesting documentary record of the importance of Patrick Geddes to civic acticism appears in an article published in 1923 in The Sociological Review, written by Mrs Victor Branford under the title Civic Revival: an account of the progress of Civic Societies. She writes that:

"At a meeting of the Sociological Society addressed by Professor Geddes on “Civics as Concrete and applied Sociology” on January 23rd 1905, Civic Societies were first adumbrated in the course of the discussion by Mr. A. W. Still of the Morning Post. He said “We may take some hope from what Professor Geddes has said that the time is coming when we shall bring the force of our characters to bear on our environment and endeavour to break away from conditions which have made us the slaves of environment…

“It has always seemed to me that there is room for good work by some body of men who would make it their business to acquire all that knowledge which Professor Geddes has first put before us in terms so enchanting and would use all the ability that they possess in order to lead the minds of the community towards the cultivation of the best and highest ideals in civic life.

“I do not think it need be regarded as impossible that from an association of this kind such a movement as I have mentioned should spring. I conceive the possibility of each group developing into a trust capable of acting in the interests of the city in years to come exercising a mighty influence, being relied upon for guidance and administering great funds for the common good… At least once a year these little groups of men might meet together at some general conference and raise up and perfect civic ideals which would be a boon to this country.”

Mrs Branford records that:

“It was not for some years after this that the Civic Society movement actually took shape and we believe that the LONDON SOCIETY led the way. Its aim as expressed in its monthly journal, of which the January 1923 number is the 59th to appear, is to “unite all Londoners who see the necessity of stimulating a wider concern for the beauty of the capital city, for the preservation of its old charms, and the careful consideration of its new developments.”

She notes that:

“The London Society arranges visits to places of interest in London and Lectures on London problems. It is at the present time publishing a valuable series of papers on “The Transport and Open Space Problem in City Development.” while its November issue also contains an article on the Roman Wall of London, thus well illustrating the combination of forelook and backlook for which the Civic Society stands.

“Its valuable plan for parkway and open space development round London which has been published and can be obtained from Messrs Stanford Ltd price £2.15 shillings is now being supplemented by a no less needed scheme for inner London. More funds are required for the completion of this much needed work.”

With the power to prepare planning schemes and the pressing need for new housing following the War, the issues that concerned civic societies were increasingly commanding public and political attention and further groups were formed to air views about the quality of housing building being undertaken by the local authorities. As the planning historian Stephen Ward has pointed out, following the 1909 Town Planning Act, the focus for activity moved away from the voluntary sector where early professionals, reformist movements and philanthropists had dominated, and into the sphere of local government where borough engineers and surveyors instead took charge of activities. In this changed organisational context, the architectural sensibilities, ambitious scale and socially informed progressivism of planners, architects and reformers found fewer possibilities for direct citizen involvement in shaping towns and cities: well-connected voluntary associations thus seemed to provide a valuable vehicle to exert influence and to act independently, notes Lucy Hewitt in her book.

Civic societies frequently had planning and related professionals among their most active members, and the meetings of societies offered a forum for lectures and discussion of planning ideas.

Further new civic societies focused on planning were formed in major British cities immediately following the end of the First World War. In Leeds, for example, the Civic Society arranged a public exhibition, held at the city’s art gallery, to promote town planning in 1919. In Birmingham the Civic Society was formed in 1918 at the same moment that the first and largest planning schemes in Britain were being set in motion. The Birmingham group used funding, made available through a Trust from the Cadbury family, to purchase land within the areas of the planning schemes and thereby safeguard open spaces from development. They also offered professionally designed schemes for the redevelopment of the central parts of small towns where the planning schemes seemed to threaten historic buildings, notes Lucy Hewitt. The Birmingham Civic Society was however also engaged in initiatives for the design of street furniture and park improvements, the redesign of the city’s telephone directory and kiosks, and even a pamphlet articulating design standards for tombstones. “The emphasis routinely stepped beyond an easy classification as part of the preservation or planning agenda, and continued earlier concerns for the aesthetics and quality of the urban environment,” Hewitt notes.

In its first annual report the Birmingham Civic Society made a clear argument about the role that a beautiful urban landscape could play in the social life of a community:

"Nothing in our modern civilization has been more mischievously underestimated than the influence of the physical aspects of a town upon the spiritual and moral life of its community. People who resent the dirt and ugliness in which a commercialised society has environed its common life, are at present forced to make their own private refuges where they can indulge their instinct for decent and beautiful surroundings...The aim of the Birmingham Society will always be to keep in mind th[e] ideal of a regenerate city."

Looking for local democracy

Further steps to support better stewardship of local places came after World War 2 ended through planning and housing reforms designed to address the rebuilding of towns and cities after their wartime damage, and to embrace new economic and social values.

By the 1950’s the Civic Society movement was flourishing in many towns and cities, and in 1957 an umbrella body, The Civic Trust, was founded by Duncan Sandys, then a British MP and former Local Government and Housing Minister who later steered the Civic Amenities Act through Parliament in 1967, establishing the concept of conservation areas as a Private Member’s Bill.

The concept of community planning was strongly further espoused two years later in the 1969 Skeffington Report,‘People and Planning Report of the Committee on Public Participation in Planning’ was prepared by Arthur Skeffington MP and the Ministry of Housing and Local Government.

The Skeffington Committee had been appointed in 1968 to assess how the public might become more involved in the creation of local development plans. This was a response to the belief that the Town and Country Planning Act created a largely ‘top down’ system, and followed the 1965 report ‘The Future of Development Plans’ prepared by the Planning Advisory Group.

Prior to this, public consultation had largely been a gesture only, involving the ‘usual suspects’, already familiar with the planning process and how to participate. At a time of slum clearances, town centre redevelopments and major road building programmes, this had resulted in poor community involvement and the emergence of a number of protest groups.

The Skeffington Report proposed that local development plans should be subject to full public scrutiny and debate. However, the recommendations of the report were not immediately taken up. They were seen as being rather vague and were misrepresented as simply advocating better public education and better communications so that it could be claimed planning decisions were well supported.

However, in the longer term, the principles that it set out became more widely accepted. Planners and developers have been pressed to become more pro-active, and to reach out so previously unrepresented and ‘hard to reach’ parts of society be better engaged. Debate nonetheless continues about how to make planning a genuinely democratic process, involving careful mediation between a wide range of competing interests.

This has led most recently to the introduction of the Localism Act in 2011, and the emergence of policies such neighbourhood planning, described by the Department of Communities and Local Government as, '...a new way for communities to decide the future of the places where they live and work'. Neighbourhood planning is intended to allow local communities to express their collective view on the important characteristics and valued elements of their areas, and how new developments should take place, and what they should look like.

However, the change is a gradual one, and neighbourhood planning has attracted criticism for being less than enthusiastically embraced by some local authorities, and by others for empowering a particular section of the community, already used to wielding influence.

The Civic Trust meanwhile campaigned to make better places for people to live through its network of local civic societies and at a national level. It ran until 2009 before going into administration due to financial problems.

This saw the Civic Trust's programmes passed onto various other organisations, including the Civic Trust Awards, continued as a separate activity; Heritage Open Days, now coordinated nationally by the National Trust; and Community Spaces, now managed by Groundwork UK.

Civic Voice, a national charity, emerged as the result of extensive consultation and discussion with hundreds of civic and amenity societies and their members and over 100 other interested organisations and partners about the future of the civic movement following closure of the Civic Trust in 2009. This work was led by the Civic Society Initiative and funded by the National Trust, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and civic societies with support from CPRE, the North of England Civic Trust, English Heritage and the RIBA among others.

The name – Civic Voice – was chosen after a ballot of over 600 civic society volunteers who selected from a shortlist of options that best expressed the intended purpose and style of the organisations. Civic Voice was more than twice as popular as the nearest alternative (Civic Vision). The body continues with the aim of making places more attractive, enjoyable, distinctive, and to promote civic pride, as the umbrella organisation for hundreds of Civic Societies and other member organisations.

Current president of Civic Voice is actor Griff-Rhys Jones. He has written that ‘if the notion of a community looking at its surroundings and wanting to control or effect it may be as old as mankind itself... from the start many wanted the place they lived in to look good and reflect its historic past.’

‘We live in cleaner, more bearable towns because of amenity groups, not despite them: because people cared and lobbied and worked to make them so,’ he says. But adds ‘The modern amenity movement may have been founded on the bedrock of simple civic needs and it may continue to sustain an interest in those needs, but we now recognise that the old enemies of neglect and local indifference have been replaced by new enemies of centralized indifference and self-interest. Today’s citizenry needed to stand out against development in the name of some obscure national interest of “economic” strength.’ Rhys-Jones notes that ‘the preservation of heritage is at the forefront of a modern Civic Society’s concerns because it is part of the current democratic pressure for civic responsibility.’

Embracing different approaches

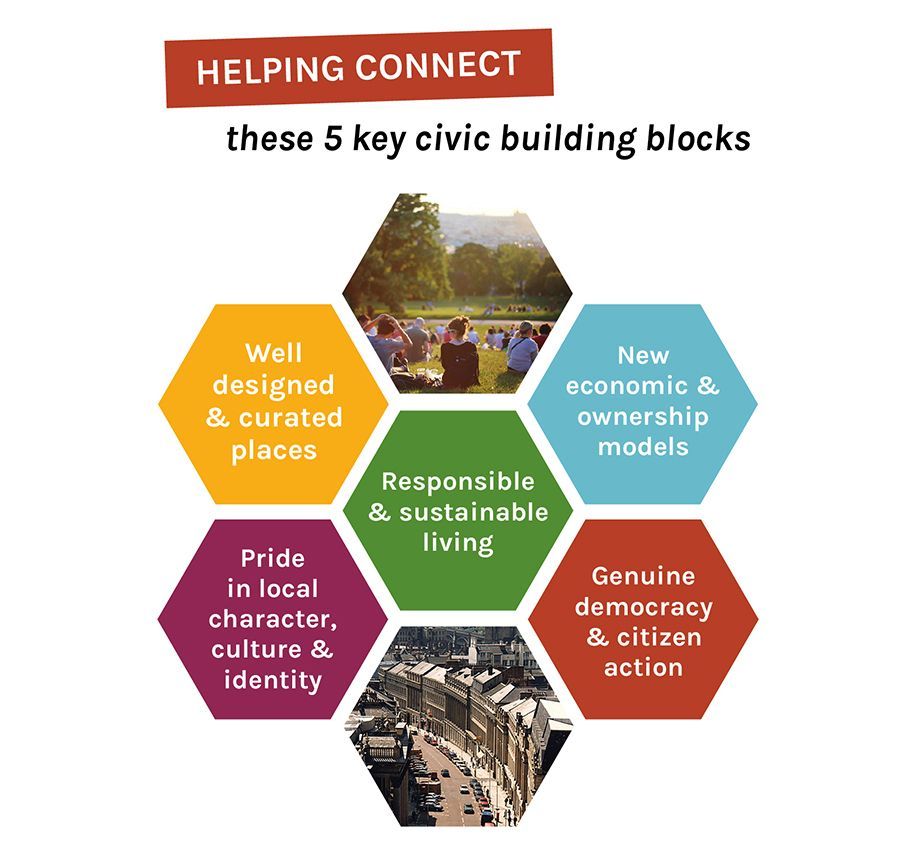

At Civic Revival we believe that the ways in which citizens engage with efforts to preserve, improve, enhance and celebrate their localities are more important, and more diverse than ever. But also more diffuse and harder to categorise and codify across the five main building blocks of mutually desirable activity we set out in our mission.

To us, it is not so important to which body civic activists belong, what structures and processes they use, or how they get things done. A belief in the importance and value of civic activism, in all its forms, is what Civic Revival seeks to support, promulgate and win greater recognition and empowerment for.

We seek to build further on the various historic steps down the path of creating more liveable communities and embracing the idea of better place-making, advocated by benevolent Victorian industrialists like Cadbury, Salt and Lever, through the visionary work of Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard and, more recently Duncan Sandys and Arthur Skeffington. We’ve recently seen other initiatives to achieve avowedly similar ends including the Localism Act of 2011 and the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, chaired by Sir Roger Scruton and Nicholas Boys Smith, that reported to DCLG at the beginning of the year.

Times change and so do circumstances, individual lifestyles and economic and social patterns, and political priorities (such as addressing climate change), but the human desire – and need – to shape the habitat in which people live and how they come together for common good remains a driving force. Civic belief and individual and collective civic-motivated activity gives substance to those vital ambitions, and is why Civic Revival now exists.