One surprising aspect of the 2020 coronavirus lockdown that was deeply felt by many, was the comfort and the joy of observing the everyday rhythms of nature in their own immediate locality.

For many of us, the limited daily routine of lockdown meant that the permitted one hour’s exercise in the local park or green space – same place, same route every day – forced us to observe nature in a single place for a significant period of time, as the weeks stretched into months.

Fortunately it was spring, the most exciting time of the year in nature. It was reassuring to see the spring come in as it always does, not only entirely unaffected by the pandemic, but actually doing quite well with those pesky humans going quiet for a spell. There was general delight across the country at the sight of the wild goats coming down from Great Orme to wander through the streets of Llandudno, or the deer coming into town to graze on the municipal verges of Romford. But everybody who got something from the ‘contemplation of nature’ side to the lockdown experience has their own unexpected ‘wildlife encounter’ tales to tell, however mundane.

Mine included being stared out by an urban fox during one of my late night forays into the streets (I eventually gave way to the fox), and being followed round my back yard every day by a robin. I gradually realised that, far from it being surprising that the robin was unafraid of me, he was actually deliberately sticking close by. Not only because I would occasionally do things of interest to him, such as pulling out a weed and exposing a little area of soil to investigate for insects, but also because I was protecting him from the ruthless killers that are the neighbourhood’s cats.

Alongside the other trends that are tipped to persist post-corona, including working from home, the decline of big city centres, and so on (as grappled with in Episode 1 of Walker’s Wanderings), the concept of a daily dose of nature as being essential for our everyday mental and physical wellbeing feels like it is a fashion likely to stick. What the Japanese call shinrin-yoku - ‘forest bathing’, or in some translations of the Japanese, ‘forest therapy’.

At the same time, the initial period following the lifting of the strictest lockdown also brought to wider attention both the need to actively look after local green spaces, and the unfamiliarity of so many people with how to behave in them. A sudden epidemic of littering on a massive scale from the new users of these spaces came as quite a shock. Reports from all over the country suggested it was a pandemic. As someone who dabbles in volunteer litter-picking, finding the weird and the gross amongst the lager tins and the chocolate bar wrappers was not a surprise, but the volume was incredible.

Civil society responded: an amazing variety of established groups and new, ad hoc community responses swung into action, and litter was picked up all over the country. (The other heroic responders, I should add, were that under-appreciated and under-paid group of essential workers, the local authority streetsweeping, refuse collection and park maintenance crews - mostly now outsourced to multinational, multibillion profit-making, outsourcing corporations - who kept on working throughout the lockdown. But that is a wandering digression.)

Finally Cummings round to the point

This Walker’s Wanderings episode is the third and last coming out of my August stay in Northumberland, and covers visits I made to Choppington Woods and Chillingham Castle.

Choppington Community Woods, in the Northumberland coalfield between Ashington and Blyth, is a woodland created during the 1970s on the site of two former coal mines, Choppington A and B Collieries, also known as High Pit and Low Pit. The woods are not a famous place at all, and are really only used by local residents. Which is exactly why I wanted to feature it - it’s an everyday place offering the everyday magic that local nature can provide.

Meanwhile, Chillingham Castle, in North Northumberland, near Wooler, is famous for having the only herd of wild cattle in Britain. It has now also become famous for being the home of Dominic Cummings’s mother and father-in-law. But it should not be confused with Barnard Castle, County Durham, which was the location of the Cummings family’s infamous mid-lockdown eyesight test and forest therapy stroll.

Choppington Woods

There are few people in the world who visit Northumberland with the ambition to visit Choppington Woods, but I am one of them. When the kids were bored, their grandma would say, why not go for a walk in Choppington Woods? We never got round to it, and it became a running joke in the family. I started using it as a threatened punishment, until the very name achieved semi-mythical status with the boys. In the 2019 summer holidays I was determined to go at last but, due to a navigational error which I refused to seek help with, the visit was abandoned, to sarcastic jubilation from the back seat of the car. So it was a great moment for me to park up the car by the Traveller’s Rest pub, and actually get there in August 2020.

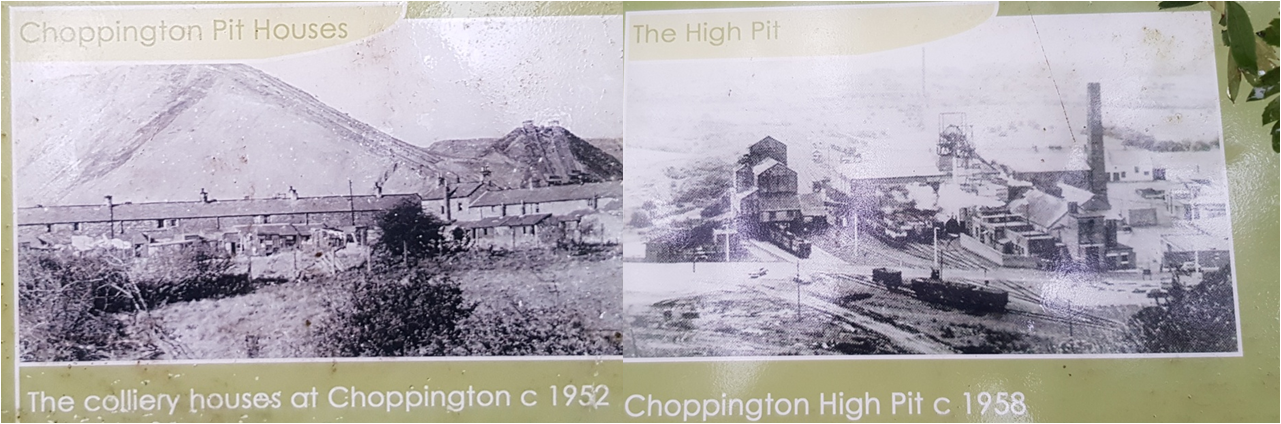

The pictures shown on the signboard show the extent of the change in the landscape since the days of the two pits.

I don’t know the full history, but after closure in 1966 and purchase of the land by Northumberland County Council in 1971, the huge pit heap was evidently levelled and fast-growing conifers planted on what would have then been poor quality and contaminated soil. This was the era of ‘derelict land reclamation’, and things were done differently then, than they would be now.

Then, all of the buildings were removed, and hardly any evidence of the two pitheads now remains. Then, the trees were planted in rows and were of a single conifer species - I don’t know if the intention was, or remains, to get a timber crop from the site. There is a map at the entrance but the paths are not waymarked, there are no facilities and, after the entrance, no further interpretation boards.

This is quite typical of 1970s industrial land reclamation, and is a big contrast to the approach taken in the later 1980s and 90s when both industrial heritage and ecological opportunities began to be more appreciated and celebrated.

For example, at Woodhorn Colliery in Ashington, which closed in 1981, all the buildings have been preserved and a really high quality museum was opened in 2006. At Low Hauxley, on Druridge Bay near Amble, which was an opencast mine, not a deep mine, the lake created has been turned by the Northumberland Wildlife Trust into a nature reserve with fantastic birdspotting hides and a high spec visitor centre and café.

At Blagdon estate, Cramlington, (privately owned by Matt Ridley aka Viscount Ridley), the spoil from another opencast mine has been landscaped to create a giant art feature, Northumberlandia, ‘the lady of the North’, a nude offering a heady mix of modern tourist attraction and reborn ancient landscape art - a wife for Dorset’s Cerne Abbas Giant, perhaps.

Back at Choppington, it should be added, quite large tracts of deciduous woodland have been planted (I think since the 1970s), which are much better for providing habitat for wildlife and producing a richer ecosystem. These trees are maturing, and are great to walk among. Choppington is not a flagship like the other places mentioned above, it's just a local nature reserve. Perhaps the lack of over-development at Choppington, and the need to investigate your own industrial archaeology, is all for the better.

Very possibly a load of bull

What about the wildlife? My guess is that the nature of the woodland at Choppington means that it is less rich in wildlife than it could and should be.

Possibly the most exciting wildlife encounter a visitor to the woods could have is with a red squirrel, which remain fairly common in Northumberland, not (yet) having been exterminated by the American grey squirrel, as is the case across most of England. If you see a grey squirrel you are asked to report it, so that someone can come and kill it!

I didn’t see a squirrel of any hue, but I did have a nice little encounter, which if not a wildlife encounter was at least a livestock encounter, which is captured in the photo below: a cow coming down for an evening drink from the Sleek Burn, which forms the southern boundary of the woods.

This got me thinking of the whole issue of rewilding, and about my family trip to Chillingham Castle and its famous herd of wild cattle, in the north of Northumberland, near Wooler. There, the willing punter pays £8.50 per head to enjoy a full safari-style experience, involving a thrilling drive through the woods and hills, to end up looking at a field full of cattle.

They are very special cattle, however, because they are the closest you will find today to the original wild cattle that roamed Britain after the ice age. They live wild, breed naturally and are not farmed for milk or meat. As a result, the herd is half males and half females. This creates a much livelier spectacle than the average field of cows, with frequent bellowings and squabbles for status among the males, which occasionally develop into full-on bullfights.

One thing about Chillingham is that the cattle roam in and out of woodland freely. At Knepp Estate in Sussex, the first large scale project in England to give up normal farming but to retain livestock on the land (with ancient breeds of cattle, pigs and ponies standing in for the wild versions of the same that would have inhabited the natural landscape), a boom in natural wildlife diversity has been observed: rare native birds, insects, flowers and so on under threat in the rest of England, all do incredibly well and a rich ecosystem is restored in the space of a few years. Knepp, by letting nature do its own thing amongst cattle and large grazing animals, is having much better outcomes in terms of thriving rare species than loads of other conventional nature conservation projects supposedly targeted at helping particular species.

Isabella Tree, chatelaine of Knepp and author of the excellent book Wilding, argues that this is because the natural landscape of lowland Britain is a mixture of woodland and pasture, containing exactly such large grazing animals, and so all the rest of the ecosystem’s species are perfectly adapted to it.

The idea that Britain was once a continuous canopy forest is a myth, she persuasively argues. Equally, we must start to think of horses, cattle and so on as creatures of the woods as well as the fields. At the end of the ice age, the big grazing animals (and the wolves and bears) came across the land bridge from the continent alongside the trees, not after them. 'How do young trees ever grow when they are subject to grazing?', people might ask, to which the answer is visible at Knepp: they emerge out of large thickets of bramble, which grazing animals avoid.

So, my little idea, very possibly a load of bull, was to wonder whether Choppington Woods - and a thousand other places like it across the country - might benefit from some thinning out of the conifers and ecosystem diversification by means of the introduction of some wild cattle, or ponies, or pigs. No doubt there a million reasons why not, many of them good ones, but rewilding is a new conservation movement for the 2020s, and some viable options for some new species must be available.

It’s a big ask of the council and local community but it’s a thought to throw into the mix. Choppington Parish Council turns out already to be an innovator: “unique in Northumberland as the only large local Council where the services provided by the Parish Council and the level of local taxation (Parish precept) are decided by local residents”.

If it increased the population of other rare native wildlife, it would certainly make the place exciting to visit. And it would be (mostly) safe: Chillingham are adamant that their pugnacious wild cattle almost always avoid attacking humans.

Civic nature

So – that’s all very nice, you may say, but what link to Civic Revival and its key themes?

Well, firstly, this is not a new thing, it’s the latest revival of a longstanding social movement. There is a long civic tradition not only of providing urban parks, gardens and allotments, but also of acquiring and managing nature reserves for wildlife and for public recreation. It’s rightly been seen as a vital aspect of a good civic life and healthy, balanced living for citizens. What is perhaps significant from the coronavirus lockdown is the rediscovery of the importance of local provision, on people’s doorsteps close to where they are.

This is a game that every town, village and city neighbourhood in the country can play: everywhere there is also some or other patch of land that formally or informally acts as a nature reserve and is used for local daily recreation that needs in some way to be actively stewarded (if only to ensure that the nature in it is left well alone to get on with its own business). There is a civic duty to ensure that all members of the community, especially those who do not have access to their own large garden, and the young (who really do appreciate nature if they can be dragged off their phones and consoles for just an hour a day), have access to ‘forest therapy’.

It is important that this is access is local. Just as we want to promote exercise, but don’t want to see traffic jams of people driving to the gym to pedal on an exercise bike, we want people to get daily access to nature without having to drive 50 miles up the motorway to overwhelm the nearest national park or stately home estate. And it is important that this access is free: we shouldn’t be having to pay an £8.50 entrance fee to get access to some natural land to take the kids for a walk. Which means that provision is best organised at some local collective or community level, either in the local public or voluntary sector.

Nature as an issue always engages a wider range of people than what we might call the ‘usual suspects’ for civic volunteering in any community. BBC Springwatch and its ilk are much watched and much loved. All kinds of people, including but not limited to pet owners, amateur naturalists, birdwatchers and so on, can be energised to get involved. In this wider appeal, the movement in some respects could resemble the similar social movement to get people engaged at the local level in community gardening, food growing, fruit harvesting, and urban farming.

An evolving tradition

In some places the lead on ‘local nature’ has traditionally been taken by charitable or philanthropic foundations, in others by local councils. In the public sector the movement to create local authority country parks was kicked off by the Countryside Act 1968, and some 250 were designated during the 1970s. In the 1990s the community forests movement got under way, and the Community Forests Trust represents nine community forests led from the local government sector, alongside the National Forest in North West Leicestershire/South East Staffordshire.

As austerity cuts to local authority budgets have taken their toll, the amount councils can do has sadly been eroded. But the voluntary, charitable and social enterprise sector has stepped up to help out with providing the stewardship that local authority parks and countryside departments have found more and more difficult to afford. County-level Wildlife Trusts, the Woodlands Trust, the Wetlands Trust and so on are well-established organisations which have grown their network of sites and projects massively in the past 15 years. Meanwhile, venerable organisations like Doncaster-based The Conservation Volunteers continue to provide an umbrella for local initiatives to get people outdoors assisting in conservation work, and getting an interesting and rewarding experience from it.

There are of course loads more individual local projects, independent local charities, entities and informal initiatives that own or manage sites for nature of various types, from the tiny to the large. But there is no more space to go further into them here.

I shouldn’t go on too much longer, but must mention rewilding, the most exciting new development in the British nature conservation during the 2010s. As a concept it was hugely popularised by George Monbiot in his superb 2013 book Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding.

Rewilding is obviously mostly a countryside thing, and is mostly spoken of in terms of taking land out of farming. But what role might it have in ex-industrial and urban fringe areas, such as the Northumberland coalfield, where quite large tracts of land – including both former coal mines and recreational country parks - are not being farmed anyway? Rewilding as a concept has run into difficulties in rural Wales and other similar places, where a lot of traditional farmers really don’t like it. Might it get a better reception in places like Geordieland?

One place that is not in Geordieland, but has a number of characteristics in common, is Oldham in Greater Manchester/Lancashire, where the Northern Roots urban farm and eco-park project for a previously neglected part of the urban fringe looks very exciting indeed.

Meanwhile, in June 2020, IPPR North published a report, A Plan for Nature in the North of England, which calls on government for a comprehensive programme of action on this issue in the North of England. It would be great if top-down action could meet bottom-up activity and projects bubbling up from the grassroots.

So there we have it: a case for making local nature and forest therapy (and maybe rewilding) a key priority for Civic Revival going forward. If you have feedback on this piece, or any information or ideas to share, do please get in touch with us, here.