This first Walker’s Wanderings offering contains musings on my personal experiences of Northumberland’s town and city centres as they were emerging from the coronavirus lockdown in August 2020.

In theory, the aim is to try to get a feel for how the big post-corona issues and potential trends are playing out in real places, and what the impact on Civic Revival’s ‘five key civic building blocks’ might be. In practice, we may wander off down some interesting-looking alleys and digress from the main subject.

The town and city centres I visited included Newcastle, Hexham, Morpeth, Blyth, Ashington, Cramlington, and Amble. They are all different, and are all likely to have quite different experiences in the post-corona ‘new normal’. How are things shaping up in each? But first, time for digression no.1.

Why aye man

Where is Geordieland and who are the Geordies? Perhaps more than any other local or regional identity in England, the Geordies know who they are, and are proud of it. Naturally, who is entitled to call themselves a true Geordie and where Geordieland’s boundaries lie are massively disputed. And, of course, it can also be disputed whether any true Geordie would ever call the place Geordieland.

Unquestionably the capital of Geordieland is Newcastle-upon-Tyne or ‘the Toon’, but then things get more complicated. How far south of the Tyne does Geordieland go? How far north and west into the countryside? In local authority politics, the North East of England Combined Authority essentially fell apart over such considerations.

We are currently in the rather ridiculous situation of Gateshead being in a different combined authority area to Newcastle, which could be compared to Salford splitting off from Manchester. The new North of Tyne Mayoral Combined Authority covers the area of the historic county of Northumberland and comprises the City of Newcastle, North Tyneside, and Northumberland council areas.

Socially, economically and politically the territory contains three very different and distinctive areas within it: the Toon and its immediate suburbs, the Coalfield, and the County, with its famous castles, beaches, countryside, moors and forests. They are all quite different, but Geordieland would not have the character it has without all three of them.

It’s perhaps surprising that such different places have agreed to combine together, but it was historically all one county, and each council is broadly comfortable with their complementary roles, as well as being firmly united in their disrespect for the new democratically elected ‘Metro Mayor’. So, is it a new workable definition of ‘Geordieland’? Maybe. But one thing is for sure, no true Geordie will ever call the place ‘North of Tyne’.

The Toon

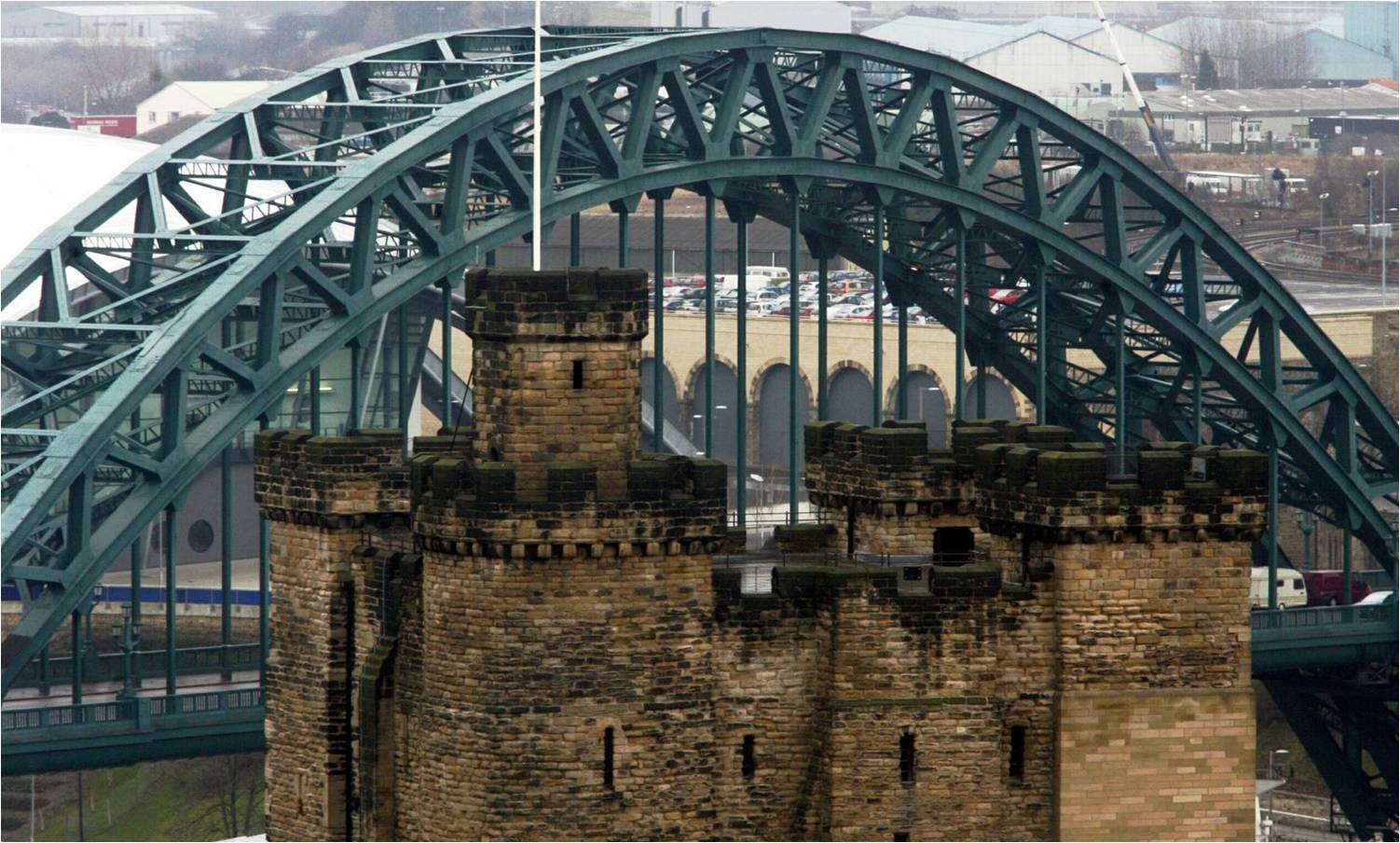

Newcastle (population 300,000) is the historic regional capital and bastion against the Scots, as well as a classic British industrial revolution manufacturing and commercial boomtown. After rough times in the 1980s, it had a good run of ‘regeneration and renewal’ in the nineties and noughties and is now basically a typical English regional core city with its shopping and leisure-based city centre, two major universities, teaching hospital, commercial and professional sector, plus its quayside yuppie flats and arts meccas, all set within a wider city of aging suburbs and long-standing inner city poverty and multiple deprivation.

Since kicking off the worldwide great financial crash on 14 Sept 2007 with the run on its own hometown bank Northern Rock (the first on a British bank in 150 years), Newcastle has given off a sense of never quite fully recovering momentum from that shock. And, like all the Northern cities where the city council has always played the leading role in civic life, the years of post-2010 local authority austerity have taken a baleful toll. But nevertheless, Newcastle always has a solidity, history and character that transcends mere financial calculations. In 2019, pre-coronavirus, the overall economic tide still felt like it was flowing in Newcastle’s direction, with a cream of hipsters selling lattes to one another sitting on top of the city’s bread and butter of white collar office jobs, higher education, and serving the people coming in from the hinterland to go to its shops, venues, bars and restaurants.

Away from the big money property developments, the city has harboured a handful of places where the creative economy, counter-culture and social enterprise were meeting the careful re-use of heritage buildings to produce a 21st century urban village atmosphere that felt good to visit and (I assume) even better to feel part of. The Ouseburn area for example, in its steep-sided gorge and with its city farm, less than a mile downstream of the Tyne Bridge, was always a joy to visit and as good as any piece of inner city ‘organic regeneration’ in the country. Ouseburn had been a Victorian hellhole of dirty industries and during the 1980s became basically derelict as factories closed down. Although it may have had its emerging problems of gentrification and rising rents, overall by 2019 it was arguably a better and more fun place to be than it had ever been.

Now, since corona, the whole 30+ year old economic ecosystem of the English core cities feels to be under a more fundamental threat than it did after 2008. The tide appears to have turned away from city centre offices and retail in a way that will persist after the health protection need for social distancing has passed. Increasing attention is now being devoted to the economic, employment and the commercial property market impacts this is likely to have (albeit with less focus so far on the knock-on impacts there may be on the banks and whole financial system). And there may yet also be disasters and bankruptcies in the university sector.

Civic Revival can’t really take these mega economic and financial issues on. Our concern must be focused on the impact on places, civically active people and the five key civic building blocks. Although Civic Revival is interested in all kinds of places and all aspects of the good curation of places and civic life, we have a particular interest in places like Ouseburn where arguably a new kind of city living and a new kind of economy was already evolving, and may offer a hopeful template for the post-corona era.

Venturing forth

It was therefore with some real trepidation that I ventured into the Toon to find out how the city is getting on as it emerges from lockdown.

The first feeling was one of relief. The good old Geordie public, who love their shopping, seemed to be out in force in the main streets of the city centre shopping core, whilst fully observing social distancing and mask requirements for inside shops. Northumberland Street and Blackett Street were busy but not packed, a feeling confirmed by a glance at Centre for Cities’ high streets recovery tracker revealing that overall footfall in the first week of August stood at 60% of pre-Covid levels. This is above average for the core cities and twice the level of London, but of course is still a level that spells financial carnage for the chain retailers if it continues.

However, in other parts of the city centre, away from the prime retail streets, shops are still closed and the street scene still has something of the feel of Danny Boyle’s film 28 Days Later. Centre for Cities’ tracker shows that the number of workers in the city centre is still down at 19% of pre-lockdown levels. Which doesn’t look good for any number of independent shops and businesses, both old and new.

Some places I looked in on like The Journey cyclists’ coffee shop next door to the Laing Art Gallery, or the mighty Geek Retreat on Grainger Street, had reopened in July and are soldiering on. At Stack, some local entrepreneurs who have taken a punt on a shipping container-based food court as a meanwhile use on the site of the old Odeon (a site forming part of Newcastle City Council’s redevelopment of the Pilgrim Street area), must be having a financial nightmare. I didn’t ask anyone how their books are looking, but it struck me that Civic Revival must be a place where we can have such a conversation.

During the lockdown a group called Tyne Collective set up a gift voucher scheme to try to help out local independent businesses with their immediate cash flow issues, with this simple pitch: “Buying a gift voucher for your favourite local business will help support them during this tough time. Your purchase directly helps businesses in need as well as giving something for you or a loved one to look forward to!”

A really great and practical piece of business first aid. And hopefully, something that will help bring the independent business community together to address the longer term business health challenges after the initial crisis. For example, to help negotiate the future relationship between small businesses and the landlords of commercial premises – the issue that is going to be at the heart of where town and city centres go next.

The only positive I could see was for the people who have really taken up proper urban living and moved into the city centre itself. They have a fantastic playground all to themselves. A hipster in hemp shorts and no shoes shot across me on an old bicycle, jumped off and disappeared through a gate into an intriguing-looking courtyard. I know nothing of him or his business, but if I was him (and if my source of income was holding up despite lockdown), then a little part of me would be slightly regretting the return of ‘bridge and tunnel’ suburbanites to my personal city realm.

How many such city centre denizens are there? Not enough, surely. Although many blocks of new flats have been built in the city centre, especially along the Tyne quayside, the conversion of upper floors of commercial buildings in the city centre to residential has been stalled for years. Grey Street may be ‘the finest street in England’ to look at, but above ground floor level it is basically sterile. If it was anywhere else in Europe its upper storeys would have a substantial resident population. It may be that the coronavirus shock to the property market will now unblock this kind of thing. The government’s planning green paper Planning for the Future makes bold claims that it will improve the planning system, but what might its effects be on places like Grey Street? This is also a conversation that Civic Revival must participate in.

Unfortunately, my family is no longer at the age where they are persuadable to visit a city farm, and so a visit to Ouseburn was struck off the agenda. Wanderer Walker will be back – and without grumbling youths in tow! The city farm is now open, with bookable visit slots and a one way system for social distancing in place, but in a charity where you need cash or the animals starve, have sadly but understandably had to introduce an entry charge for the first time.

So, what conclusion on Newcastle as it enters a new economic era? None as yet: mixed feelings. A depressing number of the small independents that gave Newcastle its charm are likely to go to the wall. But so also are some of the forces of big property development that would likely have relentlessly operated to destroy that charm. The city centre could still emerge from all this as a showcase for a new approach to sustainable living, working and playing; equally, it could emerge impoverished and decaying.

One thing is sure however: it won’t die. Newcastle has its historical longevity on its side and will endure. It has withstood sieges and outbreaks of plague before, and whatever the economic weather, the very safest bet feels to be that the Toon will be reliably heaving with revellers on a Friday night before too long.

The county

Northumberland is a big county with many delights and is far too big a subject to tackle in a short blog. This section just provides a quick snapshot of two of countryside Geordieland’s town centres, Morpeth and Hexham: two places that seem likely to be in great demand – and at risk of having their distinctive flavour spoiled - if the predicted exodus from big city centre offices happens, and more and more people among the new army of homeworkers decide to move out into the county.

Hexham is the main town centre for the Tyne Valley, and is a very historic place. Its town centre is built around its abbey which was founded by St Wilfrid in AD 674. It’s a traditional market town for a working agricultural area and it’s also an easy commute from the main Tyneside conurbation on the A69 dual carriageway. Accordingly, its population of 12,000 is a mixture of traditional country town residents and higher income managers, professionals and retirees who have moved in over the preceding decades.

Morpeth (pop 14,000), 15 miles up the Great North Road (A1) from Newcastle has been the seat of Northumberland County Council since 1980, so it might be called the county town, although others would say that that honour goes to Newcastle, or to Alnwick as the seat of the Duke of Northumberland. It’s a relative youngster compared to Hexham as its castle dates only to 1095 (only its gatehouse remains). Morpeth is bigger and closer to Newcastle than Hexham, and as a place for shopping and going out it also serves the coalfield area of South East Northumberland, and some people might say it’s barely a country market town at all. Instead, it’s an integral part of the wider Greater Tyneside urban region, with people not just commuting up and down the A1 to Newcastle but criss-crossing the whole area to work and trade on the network of fast roads.

Within this broader urban region, both Hexham and Morpeth town centres have cachet amongst all Geordies as classier than average places and are cherished for their heritage character. However, neither place is only airs and graces: you are as likely to meet young revellers in their glad rags tumbling or tottering out of the pubs on a Friday night in both Morpeth and Hexham as you are in Newcastle’s Bigg Market.

Both town centres host the large superstores which perform the role of the old town market in terms of feeding and equipping the town and surrounding villages (Hexham, Tesco Extra; Morpeth, Morrisons). Both towns have to a degree managed to locate their superstores so that they work symbiotically with the towns’ evolving traditional high street, rather than simply destroying it. Morpeth in particular has made it possible to park once and visit both the supermarket and high street without re-parking (albeit at the cost of a vast swathe of surface car parking in the middle of the town).

I don’t know how either place fared specifically during the lockdown, but in general food superstores have done extremely well in 2020. Certainly by August in Morpeth, the supermarkets were as busy as ever and many people seemed to be doubling up their trip with a trip to the high street shops, where footfall was busy.

We visited Hexham on a Saturday evening, after an evening walk along the Roman Wall. Woe betide anyone trying to get fed in a pub after 8pm in Northumberland! Your options are the chippy or the Chinese takeaway. But in genteel Hexham, a guy from Mexico City, who met a local lass in the Galapagos islands and married her, has set up a Little Mexico, a Latin American streetfood café which is open till the cosmopolitan hour of 9.30pm. Good grub at a good price, and exactly the kind of thing that is going to make Hexham an attractive target for the potential post-Covid wave of people leaving the big city. We spotted Newcastle developers Lok are marketing a conversion of the old Tynedale District Council offices as retirement homes right in the middle of the historic centre.

Eating out places in Geordieland are usually busy at the weekend but deathly quiet Monday-Wednesday. However, Dishy Rishi Sunak’s Eat Out To Help Out £10 off programme was turning that completely on its head in August 2020. Bookings were impossible to come by anywhere in the region for Mon-Weds, but availability on Thursday evening? No problem. The scheme has been criticised in a number of dimensions but without a shadow of a doubt, it has been a smash hit with the Northumberland swing voter.

Post-corona Hexham on a Saturday night had other delights to offer. A free ‘Cinema Paradiso’-style outdoor cinema screening of The Greatest Showman was showing in the abbey garden, directly opposite the wonderfully old-school newspaper offices of the Hexham Courant and the frosted windows of the Conservative and Unionist Club.

Advantage had been taken of the simplified regime for street closures to allow for social distancing, and the historic and beautiful Market Place, usually torn up by cars (as is usual across Northumberland) had been closed to traffic and opened up to café tables.

Relieved of traffic, as night fell in the atmospheric historic streets around the abbey, it was easy to be transported back a century or two. Hopefully a scheme that will be made permanent, although no doubt any such plan will be the subject of a vociferous local debate in the pages of the Hexham Courant.

By contrast in Morpeth, which is storing up all manner of future traffic problems by building out a number of peripheral new housing areas (see Episode 2 of Walker’s Wanderings), the only evidence I saw of emergency traffic measures was the banning of pedestrians from the narrow footway across the town bridge, to keep room for traffic.

If it is true that an extended craze for working from home will trigger a change in locational preferences to make the county part of Geordieland even more popular a place to live than it already is, then the question of whether the government’s planning reforms set out in Planning for the Future will accommodate that is likely to become a very high profile issue indeed.

The political drama will revolve around ‘concreting over the countryside’ and the potential voter backlash from the county’s true blue loyal Tory voters against a centrally-imposed ‘mutant algorithm’ requiring local authorities to do so. Complaints from Tory MPs have already started, and undoubtedly Northumberland’s Tory MPs will be looking on with interest.

Civic Revival is very much in favour of good new housing, but it is against new housing that is badly designed and bad for the people who have to live in it, for the places that is located in, and for the planet. Watch out for Episode 2 of Walker’s Wanderings for more on this question.

The coalfield

The impossible last word on the question ‘who are the Geordies’ should probably go to the grandmother of the leading scholar of the Geordie dialect Scott Dobson, born and bred in the ultimate Geordie heartland of Byker: her view was that “the true Geordies are the pitmen”.

The Northumberland coalfield starts at the Tyne and runs north as far as Druridge Bay on the coast. From the original ramshackle pits on the banks of the Tyne the coalfield developed northwards throughout the 19thcentury. Bigger and better pits were opened well into the 20th century and places like Ashington, “the largest pit village in the world” were operating at full pelt well into the 1970s and beyond. Famously the Northumberland mines extended out for miles under the North Sea. Although there are plenty of horrible tales of deaths from collapses and explosions, as mining engineering and safety progressed, the great boast was that the North Sea had never once flooded a Northumberland deep mine.

Year Zero of the present era in the Northumberland coalfield was the monetarists’ recession of the early 1980s culminating in the miners’ strike of 1984. The legacy of the previous era, of the NCB, the CEGB, the NUM, took a while to go but is now almost all gone. The last deep mine, at Ellington, closed in 2005. Ellington served the Alcan power station and aluminium smelter at Lynemouth, which features as a backdrop to the film Billy Elliott. The smelter continued to run on imported coal until it closed in 2012.

What grew up in its place was the post-industrial world of Silverlink Retail Park, Asda Blyth, Currys PC World Cramlington, commuters zooming up and down the A189 Spine Road and A19 to jobs in the Cobalt office park in North Tyneside. But the Geordies kept their distinctive character and arguably the coalfield became a better place throughout the ‘NICE era’ of non-inflationary continuous expansion. The environmental devastation of the pit heaps was greened over, and the best of the industrial and social heritage was preserved and celebrated in places such as the Woodhorn museum.

The coalfield has tried to keep its place as an ‘energy coast’ and at Blyth some of the future can be seen alongside the past. Alongside the old wooden coal staithes from which coal trains used to load coal onto ships for export, can be seen the windmills of the National Renewable Energy Centre’s research centre and the cable-laying ship for the new North Sea Link high voltage DC cable to Norway. It’s good to see, although the realisation that the undersea cable will mostly be importing electricity from Norway gives a little pause for thought.

A new era was also marked in December 2019 when Blyth Valley became the first North of England Labour ‘red wall’ parliamentary seat of general election night to fall to the Conservatives on a 10% swing from the Labour Party, who had held it since time immemorial. The retirement of the previous MP Ronnie Campbell, who had left school at 14 and worked 28 years as a miner, had marked the end of the previous era.

Blyth

What of the town centres of the coalfield? In Blyth (pop 37,000) the town centre has some fine heritage buildings and the added interest of a working harbour and a sandy beach. Nevertheless, perhaps fittingly as the childhood home of Mark Knopfler, it has been in and out of dire straits for 40 years. Unfortunately the Asda superstore was built a mile or two out of the town centre at the A189 Spine Road junction, and this tore the heart out of the town centre in terms of footfall. As the town centre hit the skids, it then became more and more of a no-go area for too many residents of its natural catchment area, including for the inhabitants of the many new housing developments built orientated towards the A189 and the road out.

Despite recent successes, including the Commissioners Quay Inn hotel, and the triumphant hosting of the Tall Ships Race in 2016, Blyth town centre is still a long way from being the kind of place like Morpeth or Hexham, which third agers or home-workers escaping from Newcastle might aim for, and positively want to live in.

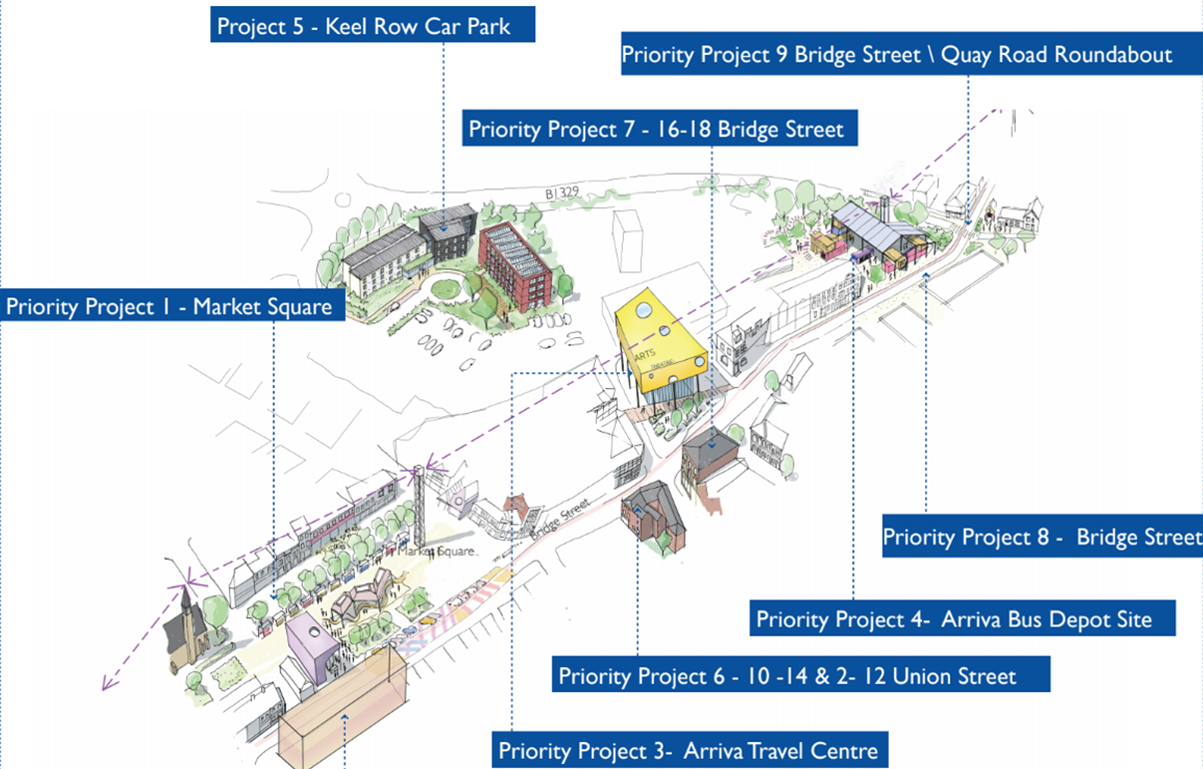

In the run up to the 2019 general election Blyth had been picked out as one of towns eligible to bid for the £3.6bn Towns Fund/Future High Streets Fund (one of a number of key Conservative target seats that went blue at the election). In August 2020 Blyth submitted its £40m bid to the Future High Streets Fund, under the highly appropriate name ‘Energising Blyth’.

Energising Blyth will be one of the government Towns Fund stories that Civic Revival will be keeping a close eye on. After December 2019 Blyth Valley is a totemic place and the story of the latest attempt to improve its town centre can be viewed as an acid test of the Government’s promises of ‘levelling up’. Look out for a future detailed report.

An early win for Energising Blyth's flagship project to revitalise the town’s market square is another travelling outdoor cinema pop-up, Movies in the Marketplace. Although, unlike Hexham, they are perhaps wisely not risking putting any shows on after dark.

Ashington

In Ashington (pop 28,000), the town centre was never an architectural masterpiece, but it was lively and full of cultural endeavour in its day, as the play The Pitman Painters attests. Now, to quote a local resident, Ashington is “shite”.

However, unlike Blyth, but like Morpeth, Ashington’s Asda is located a short walk from the traditional High Street, and just across from the very high quality new library and leisure centre, and the vacant site for what would have been the new Northumberland County Hall. This was an audacious bid by the 2013-17 Labour-controlled council administration to move the county hall from Morpeth, a decision that was promptly reversed when the Conservatives regained control in 2017. Whatever the view on this particular piece of politicking, it cannot be denied that Labour was correct to identify that something major was needed to draw anybody from outside the town to come into Ashington.

Cramlington

The final town centre in this tour of the Northumberland coalfield is barely a town centre at all. Cramlington New Town (pop 29,000) was a project conceived and nurtured by Northumberland County Council, not central government, unlike its counterpart Washington, south of the Tyne. Its 1970s era town centre shopping precinct, Manor Walks, has been entirely redeveloped into a giant drive-in shopping centre on the ‘retail park’ rather than ‘shopping mall’ design template, where you park directly in front of the store you are visiting, and re-park the car to move between different parts of the development.

Love it or hate it - and if you are a Civic Revival supporter you are pretty much obliged to hate it – Manor Walks is a classic example of the car-based ‘big box’ retail shed design format in the North East. Perhaps more even than traditional town centres, big box retailing now stands to be slaughtered by Amazon and internet shopping, and the coronavirus lockdown has hastened the death blow.

Although these retail formats are likely to be little lamented by anyone, their fate is quite important in terms of the employment future of places in the Geordieland coalfield like Cramlington. Jobs with chain retailers have in recent years formed a stable core of employment for the coalfield communities arguably to a comparable degree as the pits in the previous era, however low wage they were. They are now already being shed in waves of redundancies reminiscent of the 1980s. One of the more depressing experiences of any town centre trip these days is having to listen to shop assistants read out a script that condemns their own job to the scrapheap: “we don’t keep that item in store any more, why don’t you try online?”.

Amazon has chosen locations in Darlington and Durham for its North East England fulfilment centres, and the whole of Geordieland will be serviced from these two giant facilities. In Cramlington and across the former ‘red wall’ (now ‘blue wall’) towns, the forecast is that a hurricane of lost local incomes is approaching. In the face of it, the kind of money available from the Towns Fund is of the scale of spitting into that hurricane. What alternative options might a government which has promised 'levelling up' conjure up for people, other than the body and soul-destroying Universal Credit regime?

What the Cramlingtons of England will look like and be like after this hurricane remains to be seen, and Civic Revival will do its best to keep an eye on it.

Conclusion

So there it is, a surprisingly lengthy whistlestop wander around a fascinating part of the country, Northumberland/North of Tyne/Geordieland, with some pointers to the themes and examples that Civic Revival aims to keep reporting on.

Keep an eye out for Episodes 2 & 3 of Walker's Wanderings, also around Northumberland, covering new housing developments, and local nature reserves and rewilding.