The third discussion forum session in the series ‘Five Steps Forward for the Civic Revival’, held on 17 December 2020, turned the spotlight on the current state of the system for ‘urban regeneration’, and in particular on masterplans for the redevelopment of town and city centres across the country.

Civic activists from Hastings, London, Bradford, Crewe and Coalville shared their stories, which between them painted a somewhat depressing picture of a town planning system that seems to have lost its way, and has been captured to act in the interests of ‘big property’ money (usually based offshore), rather than giving citizens a democratic mechanism for curating the town and city environments that they want to live and work in.

Immediate feedback received was that this session broached a vital issue for the future of towns and cities in England & Wales which is of huge public concern, yet is barely discussed or analysed in the mainstream media: the dominance of the “extractive model” for development/placemaking. In 2021, we urgently need to start discussing it, not least because of the conditions of economic depression into which we will emerge from the coronavirus pandemic.

The issues raised by the testimony heard will be incorporated into the ‘Manifesto for a civic revival’ being prepared for launch in Spring 2021, and Civic Revival would be delighted to hear from civic activists anywhere in the country who wish to add to the collection of examples being assembled.

The full video of the session is posted at the foot of this report, which summarises the key points made by the eight speakers and subsequent lively discussion session.

Programme

- Hastings, Bolton, Warrington: Challenging the cult of the masterplan Peter Stonham

- Shoreditch: Stop the Monster! Lucy Rogers & Jonathan Moberly

- Elephant & Castle: Beyond Extraction Steve Taylor

- Bradford: taking back control of the planning debate Si Cunningham

- Crewe: a scheme with no legs Chris McGarrigle

- The experts respond Mo Aswat, Nick Wates

- Coalville CAN: showing a way forward? Deana Wildgoose

- Summing Up Lucy Rogers, Peter Stonham, Richard Walker

Hastings, Bolton, Warrington: challenging the cult of the masterplan

The forum kicked off with an illustrated presentation by Civic Revival Chair Peter Stonham which, with characteristic agenda-crystallising flair and thoughtfulness, examined “The Age of the Masterplan and its Discontents”.

Peter started by re-stating Civic Revival’s concept of five key civic building blocks: places, character, sustainability, local economic activity and democracy. Town planning is not one of the core building blocks, it is something that you do to get what you want, he argued. When planning is done, it needs to be a servant, not a master; however, unfortunately we live in an age where the concept of ‘masterplanning’ has become the big thing. He had decided to use this evening’s forum to consider how this has happened, what it means, and whether or not we should like it that way. After research and reflection, Peter’s personal conclusion was, he does not.

Peter’s examples of the cult of masterplan-led property development gripping the country began with an old example from “bitter personal experience” in his adopted home town of Hastings: the removal of the Central Recreation cricket ground in the middle of Hastings town centre and its replacement by a bland ‘clone town’ Priory Meadow shopping centre in 1996. Something that was unique to Hastings (“unusual and delightful”) was replaced by something completely generic.

In recent years, masterplan-led town centre comprehensive redevelopment has been touted everywhere, in places from Croydon to Bolton, Crewe and Warrington. In Bolton, the Chinese Beijing Construction and Engineering Group is the development partner for a very large and ambitious plan to demolish and rebuild swathes of the town centre. In Crewe, where the last-ditch battle to save the 1950s Royal Arcade shopping parade and clock tower was reported at the first Civic Revival forum, demolition of the buildings has now gone ahead (see the report of Chris McGarrigle’s update below).

Peter had posed the question to himself: “why do we keep smashing up our shared social and cultural inheritance in pursuit of some externally-driven conceptual vision – often, not what the local people want?”. Was he the only person who was questioning the “cult of the masterplan”? His researches had thrown up very few examples of thinkers who had challenged the masterplanning model for redevelopment, but one was the American architect Christopher Alexander, whose thinking on a more subtle and sensitive approach to placemaking (“pattern recognition”) can be summed up in the quotation “most of the wonderful places in the world were made not by architects but by the people”.

The best definition of what masterplanning is has been provided by the World Bank, and it is very much an idealised, top-down view of an orderly process for development. (The irony of the World Bank providing the definition was left unsaid – but the World Bank as an institution is the very epitome of question, whose interests does it really serve?) The key point for Peter is that this definition has become dominant, accepted seemingly without question by the professions - planners, architects, surveyors – and by politicians and the media too.

Peter argued that in Britain the practice of masterplanning has diverged from the World Bank’s ideal definition and we often end up with disasters such as bankrupted councils and ‘holes in the ground’ in the middle of our cities which last for a decade or more. He proposed a four-stage model of how it works in practice in British towns and cities, which is reproduced in full below:

- Councils are sold a vision of modernism and economic prosperity to be achieved by ‘investment in their area, and adoption of the latest stylistic designs – usually international architectural tropes – which require large footprint sites to be made available for developers to build on.

- The developers co-opt the council into their vision, and work with planning and architectural advisors to a suitable glossy and impressive Masterplan document with conceptual maps and borrowed images from other cities around the world to show just how wonderful a place the town could become.

- The council becomes the advocate of the scheme, which the developer has notionally signed up to, but no-one sees the full documentation with all the escape clauses and conditionality that will allow the project to be abandoned if all sorts of criteria fail to be met, including anchor tenants, economic conditions and commercial viability.

- The existing buildings and public spaces are allowed to decline as ‘they won’t be there much longer’ because the new scheme is coming, and often, demolition becomes the favoured option as the last available declaration of intent by the council that something better is coming soon.

Peter looked at the case of the Warrington as a place at grave risk of becoming an example of this story. The Warrington Town Centre Masterplan was launched in 2020, and is a classic example of the fine words and images that are used to get support for a plan that in all likelihood will never fully happen, and those bits that get done will not turn out to be as good as hoped. In October, parish councils in Warrington led by Cliff Taylor produced a more realistic plan for post-Covid realities, A New Plan for a Changing World, which was reported by Civic Revival here.

Peter also showed Warrington Council’s 2007 plan for the town centre’s Palmyra Square conservation area, a lovingly put-together document which shows what local authority planners rooted in their own place can really be capable of. Careful custody of a town’s character used to be a municipal mission – have the skills and experience for councils to deliver on this mission now been lost?

Peter asked whether a post-Covid downturn in the property market could see a large number of masterplans failing with councils being left holding the can of “large holes in the ground” sitting in the middle of their town centres. The list of places was long: Basildon, Winsford, Nottingham, Stockton, Bolton – and what was new was that, after a long property boom, places in London such as Croydon, Lewisham and Elephant & Castle looked like they may be joining the list.

He closed with a plea for more public debate on the pros and cons of the masterplanning approach, arguing that unexamined, it embodies the unhealthy relationship between local authorities, developers and professionals which citizens find difficult to find out about and comment upon. In the 1960s/70s local authority planners were rightly criticised for their high-handed and arrogant approach to comprehensive redevelopment in the cause of ‘slum clearance’ and better living conditions. Now they are reduced to just acting as agents of outside property developers.

Shoreditch: Stop the Monster!

Testimony from places across the country kicked off with an example of a superbly well-organised, detailed and imaginative grassroots citizens’ campaign against a masterplan, the Bishopsgate Goods Yard in Shoreditch, London. Shoreditch is where the historic old East End butts right up against global financial centre of the City of London. The Goods Yard is the site of the old British Railways Eastern Region goods station, the counterpart to Liverpool Street passenger station, which has been disused since the 1970s. The site remains in public ownership and what to do with it has been the subject of planning saga that has run for many years.

Shoreditch locals Lucy Rogers and Jonathan Moberly told the story of the campaign against the latest planning application of developers Hammerson and Ballymore, under the slogan Stop The Monster. Lucy told us that the current scheme was originally conceived in 2013 as part of the wider ‘City Fringe’ masterplan, to expand the concrete and glass office blocks of the financial industry into the fine-grained streets and highly mixed community of old Shoreditch.

Lucy explained that everything about the scheme was designed to meet the needs of big business, and nothing about it met the needs of the people in the actual place it was located in, an area dominated by small independent businesses and home to England’s oldest council estate, the Boundary Estate, built by the Metropolitan Board of Works in the 1890s.

The development scheme is the usual “city stuff” formats – expensive offices, ground floor units for chain retailers, luxury flats and a business hotel. As Jonathan’s screenshared visualisations showed, it is a gross overdevelopment of the site even by London standards, with great monsters built right up to the very edge of the site, literally overshadowing the surrounding streets and homes, blocking out all sunlight in winter.

Lucy noted that the whole story of the planning process has been about making sure the voice of the local residents would not be heard and could not get in the way of the overall City Fringe master plan, a process Jonathan called “the collapse of local democracy” and told in more detail.

The original application in 2014 had been refused by the local authorities of Hackney and Tower Hamlets, but the developers had lobbied for it to be ‘called in’ for determination by the Mayor of London, which at that time was Boris Johnson, on the assumption that he would grant it permission in the last days of his reign as Mayor. To their surprise, Johnson’s planning officers recommended the planning application’s refusal, and the developers quickly withdrew (“deferred”) the application. The developers withdrew to lick their wounds and then returned with the latest scheme in 2019, which controversially stayed with the current Mayor, Sadiq Khan, to determine, and not sent to the local boroughs.

Jonathan’s story brought out the complexity of fighting a planning battle, and the sheer stamina required to do it. That Sadiq Khan decided to give the objectors only 15 minutes to present their huge dossier of carefully prepared objections to the scheme at the official hearing on the planning application on 3 December just added insult to injury.

The campaigners reacted to this by setting up their own ‘People’s Hearing’ on the planning application, held on 30 November 2020. This online event gave all the expert witnesses against the development time to make their case and the developers were offered 15 minutes to argue for it – an offer they declined to take up. The ‘Peoples Hearing’ is set out in full in this report on the Goods Yard campaign’s website, and the video of the event can be viewed here.

The irony of the tale is that, in the post-Covid economy, it seems unlikely that the development will get built in the foreseeable future. As Lucy notes, the monster is in fact a dinosaur.

Quite possibly, the whole planning permission saga was more about preserving a fictional valuation for the site than it is about actually getting a real scheme built.

Elephant & Castle: Beyond Extraction

Steve Taylor had kindly stepped in to give the next talk, another tale of comprehensive redevelopment from London, this time from Elephant & Castle, south of the Thames in the London Borough of Southwark.

Elephant has been undergoing a process of major transformation for a number of years, including the demolition of the giant Heygate Estate and the taming of its notorious traffic gyratory and pedestrian subways. The most recent controversy has been over the demolition and redevelopment of the 1965 Elephant & Castle Shopping Centre by the development firm Delancey. One of England’s first shopping malls, in recent years it had become a centre for cafes and bars serving South London’s Latin American community [Disclosure: also serving as the venue for several discussions in the lead-up to the founding of Civic Revival].

Local resident Steve, after a long and varied career, had been inspired by the rapid changes he could see going on at Elephant to return to university in 2018 to complete a research Master’s degree on the property industry. His aim was to map the flows of money capital to, through and out of the property development going on, in order to assess the claims that the redevelopment will enhance the local economy and therefore benefit local communities.

An example of his method is the way he looked at the common claim by any council or developer that a given new development would generate a certain number of new jobs, which would benefit the local community and economy. Looking at the numbers at Elephant, Steve was able to show that a person working in any of the new retail and café units (at the going rate for wages in those trades in central London) would have to spend over 100% of their take home pay to be able to afford the rent on any of the flats in the new developments in Elephant, such as those that replaced the Heygate Estate. The workers in the new development will have no choice but to live elsewhere and commute in, and their wages will be spent somewhere else, in a different local economy.

His thesis examined many aspects of the money flows relating to the development in a similar manner. At the other end of the scale, looking at the profits flowing out of the development, Steve noted that the developer Delancey is a notorious tax avoider, with a web of companies all registered in offshore tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions. The new development will in the end be owned 50% by a Dutch pension fund and 50% by the Qatar sovereign wealth fund.

In short, all the profits from the development “will be extracted not only out of the local area, but out from the borough, out from London as whole, and head out of the UK, without touching the sides”, Steve said.

What can other places across the country learn from his research, and the experience at Elephant of a developer getting his own way despite the determined opposition of the local community? Many things, but Steve chose to focus on just one: most local authority planners know little about local economies – it’s just not part of their professional education. Local communities of course do know the realities of their local economy, but lack the framework and the language to express their knowledge. This allows the developers, often in cahoots with the local authority, to control the narrative and “paint the objectors to the scheme into a corner” - into horse-trading over relatively trivial amounts of space and development value, in this case over the size of the replacement temporary units to be granted to some, not all, long term tenants of the old shopping centre.

The central lesson Steve has learned is that the so-called economic cases need to be challenged right from the outset and an alternative economic narrative has to be at the heart of the opposition to developer-led, extractive urban regeneration. This should be based on a combination of local knowledge, informed research and experience gained from successful real-life examples of challenges to the conventional developer-led model elsewhere.

Alternative economic models are available and have been demonstrated in places as diverse as Preston, Barcelona, and Jackson, Mississippi. In his thesis Steve sketched out a completely alternative approach for Elephant, bringing together (in a utopian way) elements that have been tried and proved elsewhere, but never put all together in one place before.

Bradford: taking back control of the planning debate

Si Cunningham from Bradford Civic Society was the next contributor, and was asked to tell the saga of Bradford city centre and its famous post-2008 crash “hole in the ground” in the city centre, where a new Westfield shopping centre was supposed to go.

Si politely declined, arguing that doing justice to the saga of the “fascinating but often very troubled” city of Bradford would need ten days to tell rather than ten minutes. But he was greatly struck by the parallels between Bradford and what he observed happening in Croydon with the same developer Westfield, when he had been living there in 2015 (after other spells living in Elephant & Castle and Bishopsgate, coincidentally). The Croydon and Bradford stories had been so similar it was like watching a “City Centre Regeneration+1” television channel: everything that had happened in Bradford was being replayed over again exactly the same in Croydon.

However, the storylines diverged in 2020 when Croydon Council was effectively bankrupted by its property market speculations going wrong. Thankfully, nothing that drastic had happened in Bradford. Nevertheless, the story of a developer, in cahoots with the local council, implementing upon a city’s residents what they tell people they think they should need, rather than asking them what they would want, was the same in both places.

With due credit to the Bradford Council, it had succeeded in getting the shopping centre scheme back up and running to fill the hole in the ground, and the new 70-unit Broadway Mall was opened in 2015. The new centre has plugged gaps in the range of shops available in Bradford, but has decimated the historic shopping streets of the city centre. [Civic Revival reported on this in May 2020 here.] The decline has now become even more pronounced due to the additional hit of Covid.

Si Cunningham made an important point about a key difference between the story in London and the story in Bradford: unlike parts of London, Bradford has never been remotely close to achieving the benefits of redevelopment-led gentrification. Yet, frustratingly, the city seems to be in thrall to flirtation with the idea of economic prosperity coming through commercial development. For Si, it is never going to happen on the scale that the city’s leadership wants it to, for reasons which include the city’s proximity to Yorkshire’s commercial capital Leeds.

Nevertheless, despite being very poor, the city has tremendous opportunities: the average age of its population makes it the one of ‘youngest cities’ in Europe, and there is amazing potential for the reuse of the city’s architectural heritage assets for real community-powered interventions.

When the Civic Society did an exercise earlier in 2020 to ask people what they liked about their city centre, the response was negative about generic ‘cookie cutter’ shopping projects; instead, people looked for changes to the city centre that added green space and showed off the city’s world-famous Victorian architecture. Although the ten years of Westfield’s famous hole in the ground was a terrible thing, it did expose the previously concealed Little Germany quarter of the city centre, one of the finest merchants’ quarters in Europe. At the time some had suggested leaving it as an open space, for a new park.

There is now an opportunity in Bradford to have another try at a people-powered approach to city centre regeneration: when Westfield were developing the Broadway Mall, British Land snapped up a large five acre plot next to the site purely to stop Westfield buying it and being able to expand into it. A ‘could be anywhere’ scheme by British Land to develop a cinema and bowling alley on the site is now dead in the water post-Covid, and the city once again finds itself in the position of having a big hole in the city centre and being able to ask “just because we can fill it with something, does that mean we should?”.

The opportunity now is to “take back control of the discussion”. Although there are many good people in the council, they and the private developers speak “almost their own secret language”, and use it quite cynically when it comes to public consultation: they ensure there is no room for the public to dare suggest what they might want to see. This site is Bradford city centre’s new planning battleground, and Si is looking to help the citizens of Bradford to become more assertive about demanding what they want, rather than just asking to be consulted. In this new approach is the secret of how Bradford can thrive in the future.

Crewe: a scheme with no legs

Next up was Chris McGarrigle, the chartered surveyor who had introduced the first Civic Revival discussion forum to the battle to save the Royal Arcade building in Crewe in October (reported here). Chris’s story had raised so many issues about ‘big property dinosaurs’ that the subject of this third discussion forum had been amended to look into them further.

Chris told the full story of the Crewe town centre Royal Arcade development. The buildings which have now been demolished were opened in 1957 as (what was then) a state of the art shopping facility and town bus station, on the site of a demolished area of classic Crewe railway workers’ terraced cottages. (A few such cottages still survive, if not thrive.) The developer was Ravenseft Ltd, which is now part of Land Securities.

In the 2010s the property was sold for £12m to a Manchester-based company called Modus, which soon went bust - in part because of money lost in Bradford, coincidentally. It then went into the possession of the banks, which sold it to Cheshire East Council for £6.8m three years ago. Although the banks had taken a bath on the original £12m sale value, at £6.8m the council had almost certainly overpaid on what it was really worth. Already at that time, retail rent values in Crewe town centre were close to nil.

Cheshire East Council, looking to turn the fortunes of the town centre around, boldly went forward and sought a development partner for the site. They got one offer, from a Midlands-based consortium headed by Peveril Securities, who developed and then launched the scheme for a cinema, bowling alley, multi-storey car park and replacement bus facility.

Even before Covid, Chris was firmly of the view that this proposal would never get built. Retail and leisure rental values were already dropping, and then the Covid lockdown in March 2020 put paid to any prospect for the scheme “stone dead”. Chris attempted to be a good citizen, and tried to stop the council from getting too deeply committed to “a scheme with no legs”. He wrote to the council and to the local newspaper. He heard about the new Crewe ‘Town Deal Board’ about to be appointed (a requirement for accessing the new government’s Towns Fund – see Civic Revival reports here and here), and tried to get on it, in order to advocate that a ‘Plan B’ for a modest, realistic refurbishment and reuse of the buildings should be prepared. But he was told he was “too much of a big mouth” to be allowed on it.

Instead the new Town Deal Board was appointed with “the usual suspects”, including the local MP – the newly elected (December 2019) 'blue wall' Conservative Kieran Mullan. The Board and the council have pressed ahead with the scheme during 2020 and took the decision to move to the ‘point of no return’: to demolish the old buildings, which they are now doing. During 2020 Chris tried to thwart them, for example by attempting to get the existing building listed by Historic England, which failed.

Throughout all, what baffled Chris the most was, that although any normal person would easily be able to grasp his straightforward argument that the proposed scheme had no legs, not a single member of the town’s civic leadership was able to see the reality, or even to engage with it. What is going on? His “head was in his hands”: how could they possibly convince 14 new Town Board members that this scheme was ever going to go ahead, and therefore agree to demolition and clearance of the site? The two contracts already signed for the cinema and bowling alley are conditional, and the prospective tenants will undoubtedly now be able to pull out. Not a single other prospective tenant has signed up for the scheme.

Instead, the Board and Council have signed off on a flurry of publicity announcements that preserve the obvious fiction that a fab new scheme is coming, ‘step one’ in a wider regeneration programme, and so on. Chris has become dejected, fed up with trying to rebut the publicity and get people to engage with the reality. He believes he will be able to have the epitaph “I told you so” carved on his tombstone, but that is cold comfort.

Crewe is now past the point of no return: it will now have a “hole in the ground” for many years, as Bradford once did. Why are elected politicians – Conservative and Labour alike, and others – so determined to refuse to look at the reality? Where is this going and how can we stop it?

The experts respond: Mo Aswat and Nick Wates

Richard Walker then turned to two planning experts to respond to what they had heard from the speakers: Mo Aswat of The Mosaic Partnership and Nick Wates of Nick Wates Associates.

Batley born and bred Mo Aswat is the founder director of the Leicestershire-based place management consultancy Mosaic, which works around UK and abroad including in the USA, Singapore and Gibraltar. He is one of the panel of go-to experts assembled by the High Streets Task Force to advise on towns on the preparation of Town Deal bids.

Mo set out his view that the Covid pandemic has massively accelerated trends that were already in place regarding the future of town centres. We have arrived early at a place that we would have got to anyway in a few years’ time. A host of reports, including by Portas, Timpson and Grimsey (the latter reported on by Civic Revival here) have all been saying the same thing for 10 years: that a new High Street needs to be born. Covid has brought matters to a head and arguably we have now arrived at a moment of unique opportunity.

All the enlightened developers know the clone town development model is broken, and of the 40 or so financial institutions in UK that have in recent years lent money to finance retail development, currently only two are still willing to do so. Meanwhile, during 2021, about £10 billion of existing lending to retail property is coming due and will need to be refinanced. It’s very uncertain how that will be done.

Mo noted that the only actors currently investing in town centres are local authorities, who have been buying up shopping centres and so on – a situation which worries him somewhat, and which ought to be more widely discussed.

Mo was less convinced by the argument that there is a big conspiracy between council planners and big developers, particularly not outside of London – at least “not one that has any strategic element to it”. His sense is that one place to look for answers as to what is happening is the increasing prevalence of the planning system being tied up in lawyers and litigation. In the last ten years, 50% of the major retail planning application decisions have been made by lawyers, not by planners. Developers know that if they don’t get what they want through negotiation with council planners, they can get what they want in the end by challenging decisions through planning appeals to national government, and through the courts. Local authorities no longer have the resources (money or staff) to prevent being worn down by the developers.

Looking at other changes that need to be made to revive town centres, Mo suggested looking at reform of business rates – the current regime does not encourage entrepreneurs and smaller businesses. Also, the current way of doing property leases in UK is antiquated and over-complicated: a lease contract that is 10 pages abroad is 60 pages long here. Too many leases are too inflexible and ask too much of the tenant.

If we are going to do things differently emerging from Covid, we are going to have to take a more wholesale approach to reform than that just limited to planning reform.

Civic Revival’s community planning guru Nick Wates kept his reaction brief. What an incredible mess our town centres are in, he lamented. The one contribution he could make now was to observe that it is so obvious that the answer has got to be a collaborative exercise. In any given town, the residents need to be involved, as do the developers and the planners. People have got to start working together. There were many experiments in this in the past, but depressingly it seems that the lessons from them have not been learned. He ended with a plea – please can civic activists look out for examples of places anywhere where people are working collaboratively now to create beautiful towns and cities.

Coalville CAN – showing a way forward?

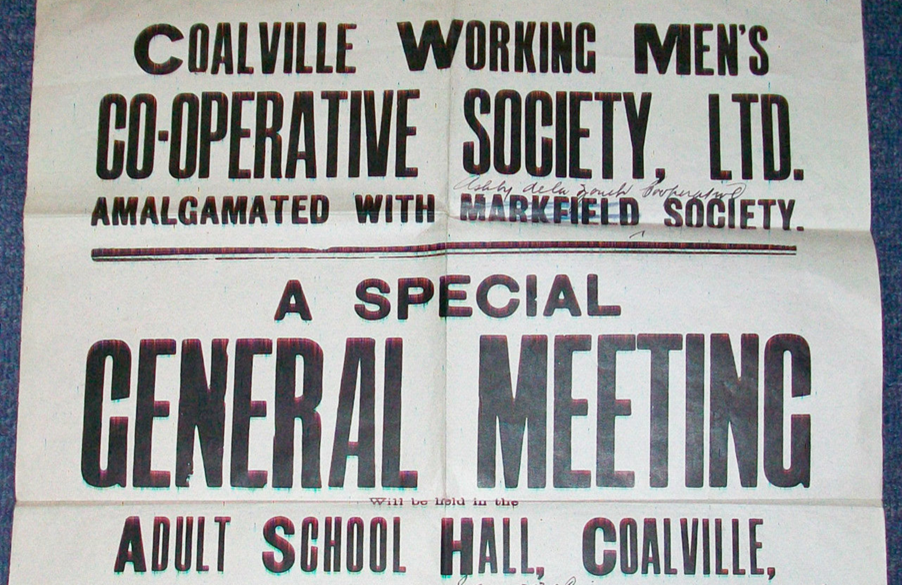

Friend of Civic Revival Deana Wildgoose of Coalville CAN took on the challenge of showing one possible model for doing better that is gaining traction in North West Leicestershire: bringing unwanted town centre buildings into community ownership through community benefit societies. Great things are afoot in Coalville which Deana believes can provide a model that can be replicated in many other places.

Deana shared a snippet of a recent presentation from Coalville CAN to local councillors - in short, it is a means of creating an ethical landlord that nurtures rather than exploits new enterprises, and uses the rents on its premises to generate a community wealth fund. (they also recorded another presentation with guests from a parish council that had set up a community benefit society and taken on a Public Works Board loan – "What every parish council should know").

Coalville CAN is looking at taking on premises in Coalville including the town’s old Co-op department store and the municipal market hall. It has proof of concept and now needs funding – a strong, innovative and community backed plan that is gaining traction.

Deana also shared some of the resources that Coalville CAN uses to engage the local community in its plans for the town, including ‘Community Asset Bingo’ and ‘the Wicked Spreadsheet’, to assess the viability of social enterprise proposals that involve taking over a property.

Coalville CAN is now collaborating with Power to Change to make a video which sets out its approach and its plans – which will come out soon in 2020. Watch this space!

Summing up

Lucy Rogers and Peter Stonham summed up the session and suggested that one way forward was to widen understanding – especially among planners and local politicians, who really ought to know better – of how the system really works and what is really going on. The only solution is to let daylight in to the closed processes currently ruling the fate of our town and city centres.

Discussion session

An enjoyable informal discussion followed with contributions from Michael Mulvey and colleagues from the Independent Constitutionalists UK (Carol Evans, Barnaby Flint and Fred Harrison), Giles Semper from Go! Southampton BID, Della from Elmbridge Community Assembly, David Gee from Bexhill Seafront Group, Peter Tyzack from Pilning & Severn Beach Parish Council and Jonathan Moberley of Reclaim Bishopsgate Goods Yard.

The video

- Hastings, Bolton, Warrington: Challenging the cult of the masterplan Peter Stonham 00:00 – 16:50

- Shoreditch: Stop the Monster! Lucy Rogers & Jonathan Moberly 19:10 - 29:30

- Elephant & Castle: Beyond Extraction Steve Taylor 29:30 - 40:10

- Bradford: taking back control of the planning debate Si Cunningham 41:30 - 49:10

- Crewe: a scheme with no legs Chris McGarrigle 49:18 – 59:24

- The experts respond Mo Aswat 1:00:25 – 1:07:56; Nick Wates 1:08:11 – 1:10:30

- Coalville CAN: showing a way forward? Deana Wildgoose 1:10:30 – 1:15:15

- Summing Up Lucy Rogers, Peter Stonham, Richard Walker 1:15:15 – 1:22:41

- Informal discussion session 1:22:41 – 1:56:56